Intravenous cannulation in prehospital settings enables the delivery of medicine, intravenous fluids, anesthesia, and other interventions prior to patient transportation (Prottengeier et al. 2016).

However, cannulation may be difficult and is associated with a high risk of complications. If the cannulation fails, this may further delay treatment and transport, potentially resulting in adverse patient outcomes (Prottengeier et al. 2016; QAS 2022).

How do you tell whether cannulation will be ‘difficult’, and how does this affect patient management and clinical decision-making?

What is 'Difficult' Cannulation?

Difficult intravenous access (DIVA), or difficult peripheral intravenous cannulation (DPIVC), describes a situation wherein a practitioner is having difficulty gaining peripheral vascular access, often because the patient's veins cannot easily be seen or felt (Rodriguez-Calero et al. 2020; Sou et al. 2017). It is generally defined as:

- Two or more failed cannulations, and/or

- Needing to use advanced or rescue techniques to gain peripheral vascular access.

(Rodriguez-Calero et al. 2020)

Difficult cannulation is troublesome for a number of reasons:

- It causes additional anxiety and distress to the patient

- It is painful for the patient

- It causes the practitioner to become frustrated and flustered

- It may delay treatment and diagnosis

- It may not allow for appropriate rehydration in time

- It may damage the vascular walls, making subsequent attempts more difficult

- Children may develop a fear of needles, complicating future cannulation

- Escalation to a central venous access device (CVAD) may be required

- Multiple cannulation attempts increase the risk of phlebitis, thrombosis, infection and other complications that may cause the device to fail

- It reduces the overall quality of care.

(Sou et al. 2017; Sonosite 2018; Rodriguez-Calero et al. 2020; RCHM 2019)

Environmental factors such as poor lighting - which may be impossible to control in prehospital settings - may also contribute to poor vein visibility (Prottengeier et al. 2016).

Which Patients are 'Difficult' to Cannulate?

Patients who might be difficult to cannulate include:

- Patients who have undergone frequent recent cannulations (e.g. patients with renal impairment or a history of intravenous drug abuse), as they may have fewer suitable veins left to access

- Obese patients or patients who have recently undergone chemotherapy, as intimal damage or altered subcutaneous fat distribution may make their veins more difficult to locate

- Underweight or premature infants who have extremely small veins

- Infants and children due to smaller veins, lower pain tolerance and susceptibility to emotional distress

- Patients with darker skin, due to decreased visibility of the veins

- Patients with fragile skin

- Dehydrated patients

- Patients in shock

- Patients living with chronic illness

- Patients who have edema, which may cause poor vein visibility or palpability.

(Emcare 2016; Lamperti & Pittiruti 2013; Sonosite 2018; Chiao et al. 2013; Olberon 2017)

Calculating a DIVA Score for Paediatrics

The difficult intravenous access (DIVA) score can be used to predict the likelihood of failing an initial cannulation in pediatric patients (Shaukat et al. 2019).

This is an important tool, as multiple attempts at cannulation may cause distress and pain to children (RCHM 2019).

If the patient scores four or more points in total, the initial cannulation has a greater than 50% chance of failing (RCHM 2019).

| Predictor | 0 Points | 1 Point | 2 Points |

| Visible vein | Visible | - | Not visible |

| Palpable vein | Palpable | - | Not palpable |

| Patient's age | Over 36 months | 12 to 35 months | Under 12 months |

(Adapted from RCHM 2019)

Performing an IV Cannulation in Prehospital Settings

For a comprehensive guide to IV cannulation, see Venepuncture: Phlebotomy and IV Cannula Insertion.

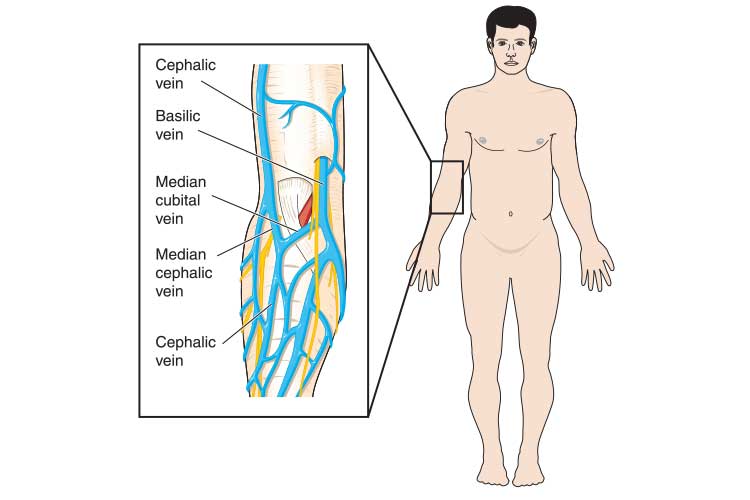

Options for cannulation sites in prehospital settings include:

- Metacarpal and forearm veins, which are easily accessible in prehospital settings and suitable for non-emergency intravenous therapy.

- Antecubital fossa (ACF) veins, which are the most appropriate option for rapid fluid administration.

- Foot and hand veins, which should only be considered as a last resort due to increased risk of infection.

(QAS 2022)

In critical emergency situations, the cannulation of the jugular vein may also be considered. It is, however, important to posture the patient properly in order to minimize the risk of air emboli.

Should all IV cannulation attempts fail, then intraosseous access via appropriate devices (e.g. EZI-IO) is a viable option. In some jurisdictions, this is already the go-to method in cardiac arrest.

Generally, the most suitable site for pediatrics is the dorsum of the non-dominant hand (RCHM 2019).

For Adults:

You should make a maximum of two cannulation attempts (refer to your organization's policy) (QLD DoH 2015).

For Pediatrics:

Assess the urgency of the situation. If the patient immediately requires IV access (critical situation):

- You should make a maximum of two attempts within 90 seconds before escalating.

- Consider intramuscular or subcutaneous bolus access using an appropriate intramuscular needle.

(RCHM 2019)

Troubleshooting Cannulation Difficulties

Note that the use of the following strategies will depend on the urgency of the situation and the patient's condition.

General Tips

- Apply the tourniquet early.

- Gently tap the vein to make it bigger.

- Try releasing the tourniquet and reapplying it. This will cause blood flow through the tissue that has been made ischemic, and a release of histamine that will help make the vein more prominent.

(Tan et al. 2015)

The Patient is an Infant

Cannulation can be distressing for infants. The following tips may help the patient feel more comfortable:

- Swaddling the patient.

- If possible, ensure the thermal environment is neutral and prevent cold stress.

- Shield the patient's eyes from bright lights.

- Allow non-nutritive sucking from a pacifier.

- Administer pain relief.

(Starship 2021)

The Patient is Overweight

It may be worth assessing whether it is possible to delay cannulation until IV access can be established using ultrasound guidance in the hospital, as this will be easier. You may also consider:

- Intraosseous insertion (with the proximal humerus providing most likely the best option in the presence of massive fatty tissue).

- Alternative routes such as intramuscular and intranasal (e.g. Fentanyl IN).

(QAS 2021)

Difficulty Dilating the Patient's Vein

Vasomotor changes due to the patient being cold, hypotensive, or nervous may mean the veins require more time to dilate. Try:

- Positioning the patient's arm below heart level or letting it hang down.

- Warming the skin by gently rubbing or stroking.

- Covering the patient's arm with a warm towel.

- Applying heat to the arm.

- Encouraging the patient to open and close their hand.

(Emcare 2016)

Difficulty Puncturing the Vein

You may accidentally pass the cannula through the opposite wall, which will cause blood backflow to cease when you remove the stylet. Try:

- Slightly retracting the cannula until flashback appears again.

- Leveling off the angle, advancing the cannula into the vein, and removing the tourniquet.

(Emcare 2016)

Never attempt to reinsert the stylet.

Cannula Insertion Failure

Try adjusting the angle of entry. Remove and reassess if this still proves unsuccessful. Remember not to make more than two attempts at cannulation (Emcare 2016).

Difficulty Advancing the Cannula

Attaching a saline-filled syringe to the catheter and gently flushing may help. If you feel no resistance, you can advance the cannula while continuing to flush. If this is unsuccessful, remove the cannula and try a different site (Emcare 2016).

Patient has Fragile Skin

This increases the likelihood of tissue trauma and cannulation failure. Try:

- Using the smallest cannula available.

- Warming the skin to encourage vein dilation.

- Using minimal tourniquet pressure.

- Decreasing the angle of entry.

(Emcare 2016)

Venous Spasm

During cannulation, the vein may involuntarily contract, causing sharp pain and skin blanching. This may result in trauma. Try:

- Applying a warm compress to the affected site.

- Choosing a different site if unresolved.

Note: This article is intended as a refresher and should not replace best-practice care. Always refer to your organisation's policy on IV cannulation.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

What is the maximum amount of cannulation attempts that should be made for a paediatric patient?

Topics

References

- Chiao, FB et al. 2013, ‘Vein Visualization: Patient Characteristic Factors and Efficacy of a New Infrared Vein Finder Technology’, British Journal of Anaesthesia, vol. 110 no. 6, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S000709121753857X

- Emcare 2016, IV Cannulation Training Pre-Course Workbook, Emcare, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.emcare.co.nz/uploads/1/1/4/8/114818101/emcare_iv_cannulation_workbook.pdf

- Lamperti, M & Pittiruti, M 2013, ‘II. Difficult Peripheral Veins: Turn on the Lights’, British Journal of Anaesthesia, vol. 110 no. 6, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.bjanaesthesia.org/article/S0007-0912(17)53849-0/fulltext

- Olberon 2017, Children's Cannulation: What is the Problem?, Olberon, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.olberon.com/single-post/2017/02/22/Childrens-cannulation-What-is-the-problem

- Prottengeier, J, Albermann, M, Heinrich, S, Birkholz, T, Gall, C & Schmidt, J 2016, ‘The Prehospital Intravenous Access Assessment: A Prospective Study on Intravenous Access Failure and Access Delay in Prehospital Emergency Medicine’, Eur J Emerg Med., vol. 23 no. 6, viewed 19 October 2023, https://journals.lww.com/euro-emergencymed/abstract/2016/12000/the_prehospital_intravenous_access_assessment__a.8.aspx

- Queensland Ambulance Service 2022, Clinical Practice Procedures: Access/Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Insertion, Queensland Government, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.ambulance.qld.gov.au/docs/clinical/cpp/CPP_Intravenous_PIC.pdf

- Queensland Ambulance Service 2021, Other/The Bariatric Patient, Queensland Government, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.ambulance.qld.gov.au/docs/clinical/cpg/CPG_The%20bariatric%20patient.pdf

- Queensland Department of Health 2015, Guideline: Peripheral Intravenous Catheter (PIVC), Queensland Government, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/444490/icare-pivc-guideline.pdf

- Rodriguez-Calero, M A et al. 2020, ‘Risk Factors for Difficult Peripheral Intravenous Cannulation. The PIVV2 Multicentre Case-Control Study’, J Clin Med., vol. 9 no. 3, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/9/3/799

- The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne 2019, Intravenous Access - Peripheral, RCHM, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/Intravenous_access_Peripheral/

- Shaukat, H et al. 2019, ‘Utility of the DIVA Score for Experienced Emergency Department Technicians’, Journal of the Association for Vascular Access, vol. 24 no. 4, viewed 19 October 2023, https://meridian.allenpress.com/java/article-abstract/24/4/38/435096/Utility-of-the-DIVA-Score-for-Experienced?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- Sonosite 2018, When IV Insertion Seems Impossible, Sonosite, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.sonosite.com/au/blog/when-iv-insertion-seems-impossible-0

- Sou, V, McManus, C, Mifflin, N, Frost, S A, Ale, J & Alexandrou, E 2017, ‘A Clinical Pathway for the Management of Difficult Venous Access’, BMC Nursing, vol. 16 no. 64, viewed 19 October 2023, https://bmcnurs.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12912-017-0261-z

- Starship 2021, Intravenous Cannulation in Neonates, Starship Hospital, viewed 19 October 2023, https://www.starship.org.nz/guidelines/intravenous-cannulation-in-neonates/

- Tan, A, Edwards, J & Downey, R 2015, Cannula Tips and Tricks, Onthewards, viewed 19 October 2023, https://onthewards.org/cannula-tips-tricks/

Additional Resources

- Clinical Practice Procedures: Access/Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Insertion | Queensland Ambulance Service

- Intravenous Access - Peripheral | The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne

- Venepuncture: Phlebotomy and IV Cannula Insertion | Ausmed Article

- Peripheral Intravenous Cannulation | Ausmed Course