Congestive heart failure is not a disease; rather, it is a cascade of events and ill-conceived compensatory efforts made by the body in an attempt to maintain an adequate ejection of blood from the left ventricle.

The heart is doing its best… but in the long run, it’s making a bad job worse.

So, what’s to blame for this common condition? After all, congestive heart failure was not built in a day. In fact, there are at least 10 diseases and conditions that can lead your patients down the slippery slope to heart failure.

Hypertension

What is the single greatest thing individuals can do to avoid heart failure? Control their blood pressure.

Hypertension is heart failure’s number one precursor. Almost three quarters of individuals who develop heart failure have a history of high blood pressure.

So, why does high blood pressure create an environment so conducive to heart failure? The narrowed arterial pathways reduce the blood’s ability to travel through the body smoothly. So, when arterial pressure is high, the heart must work harder (read: too hard) to eject volume.

Think of your heart as that bodybuilder at the gym. The heart wants desperately to keep up with the resistance being thrown its way. To cope with this extra resistance, the heart bulks up (much like the bodybuilder), stiffens up (ditto) and - eventually - peters out. It becomes less able to do its job; not more.

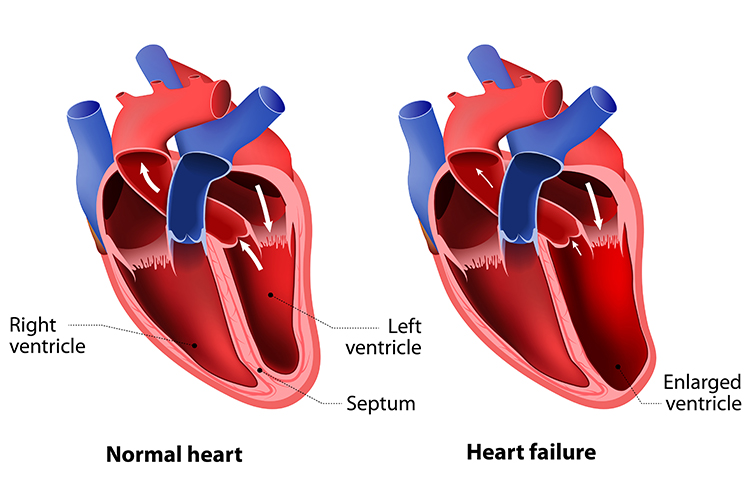

Because of the increased pressure in the Aorta and pulmonary arteries, the ventricles have to increase pump action (contractility), which leads to hypertrophy (thickening of the walls), thus decreasing the ability to pump effectively. The reduction in ejection volume (ejection fraction) creates pressure in the ventricles to build, and this has a backwards effect: pressure in the atria increases, leading to pulmonary and systemic congestion - or congestive heart failure. The increase in volume in the ventricles and atria leads to stretching of the walls or dilation/dilatation, the end-stage of the heart failure.

Read: Heart Failure Readmission and Rebound Hospitalisations

Additionally, the abnormal pressure in the arteries shreds the insides of the vessels themselves. The arteries develop micro-tears in the walls and scar over.

As is true anywhere in the body, scar tissue does not distend or stretch. There is no play or give in the artery wall… and that translates to even more micro-tearing.

It only gets worse. The pitted arteries then become perfect host sites for fat, cholesterol and other yish (commonly referred to as 'plaque') to lodge. The combination of these forces produces a stiff artery with a narrow lumen, which is the first act for peripheral artery disease (if it occurs in the periphery) or coronary artery disease (if it occurs in the vessels supplying the heart).

Both PAD and CAD produce a multiplying effect. Blood clots are birthed by the intermittently stagnant and chaotic flow of blood through plaque-filled vessels. The heart tissue, starved by lack of flow through the coronary vessels, becomes ischaemic, leading to infarction and tissue death. And a heart with a damaged ventricle is a pumping organ prone to… well, not pumping.

The spiral continues. The heart is only one of the organs affected. Damaged and hardened arteries can lead to massively wounded organs throughout the body. Because the arteries supplying the body’s organs are not functioning adequately, they fail to deliver oxygen efficiently. Over time, this can result in organ damage, such as kidney disease.

In fact, the most common cause of chronic kidney disease is long-term, uncontrolled hypertension. The heart and the kidney are intricately married, relying on each other for systemic support that, frankly, does not come. This fact leads us to our discussion of renal insufficiency as another building block for heart failure.

From here it goes downhill. Everything becomes more pronounced and exertion dyspnea (breathlessness) increases to stage-four heart failure.

Renal Insufficiency

Which came first, the damaged kidney or the damaged heart?

Truthfully, it’s hard to say. Evidence is mounting that chronic kidney disease is itself a significant player in severe cardiac damage and, conversely, that congestive heart failure is a major player in chronic kidney disease.

There is a vicious cycle between a damaged kidney, a damaged heart and anaemia. Each condition exacerbates the status of the other two. Unfortunately, anaemia is seriously under-recognised and under-treated in this population.

There is also a vicious cycle between kidney failure, heart failure and lung disease - specifically ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome), as the toxins released into the bloodstream have a detrimental effect on the artery walls and lung vessels and tissue.

Damaged Heart Tissue (Myocardial Infarction)

Apart from hypertension, the most common risk factor for CHF is an antecedent myocardial infarction (MI). Worse, the development of heart failure after myocardial infarction serves as a negative 'sentinel event'.

Why? When the heart suffers an 'attack' resulting in cardiac tissue death, the damage creates a cascade of events.

If the infarction takes place in the ventricles, the heart loses some of its ability to contract, effectively reducing its pushing capacity. In addition, over time, the area of damage scars over. This prevents the ventricle from expanding, decreasing the capacity of the chamber to accept blood (pre-load). A ventricle that can’t accept blood from the atrium is a ventricle that cannot do its job.

Truly, myocardial infarction deals a double blow to the heart - creating both the inability to accept load… and the inability to forcefully eject that load (Cahill & Kharbanda 2017). At this point, the heart sadly, inevitably, begins to fail.

Coronary Artery Disease

Coronary artery disease occurs when the vessels that supply the heart’s muscle with oxygen become obstructed with atherosclerotic plaque.

Often, the resulting coronary artery disease leads to a heart attack which - as just discussed - means that sometime in the next five years (for most people), a diagnosis of HF looms large.

Abnormal Heart Valves or Chambers (Congenital or Acquired)

The heart’s four valves must work in tandem for the heart to effectively pump blood (NHLBI 2022a).

Congenital valve defects, infections and age-related deterioration can cause any of the four valves to malfunction. And whenever a valve fails to function properly, the heart must work harder to achieve an adequate ejection fraction.

There are three potential problems with heart valves: regurgitation, stenosis and atresia.

Regurgitation is often referred to as 'backflow'. Because the valve isn’t able to close properly, blood flows back into the chambers instead of forward through the normal pathways. Mitral valve prolapse, a common type of valve defect, is one kind of regurgitation.

In contrast, valves that are stenotic do not open properly, creating havoc with the heart’s normal rhythm. They are too stiff or thickened to fully open, preventing adequate flow. Some valves can even fuse over time.

Finally, atresia is a condition in which the valve is abnormally closed or absent. This type of valve defect is often congenital and is often repaired immediately upon birth - or even in utero.

Some people live with a faulty valve their whole lives and don’t even know it. For others, heart valve disease worsens over time, producing noticeable symptoms. If not treated, a condition such as aortic stenosis can lead to heart failure.

Heart Arrhythmias

The rhythm of the contracting heart needs to be predictably regular in order for the organ to push blood. Arrhythmias prevent this from happening, either because they slow down the heart (bradycardia), speed it up (tachycardia) or otherwise create an abnormal contraction pattern.

Arrhythmias are most feared for their role in sudden cardiac arrest (SCA). In SCA, the heart’s electrical system malfunctions and suddenly becomes very irregular.

Typically, the heart speeds up to a dangerous pace and the ventricles begin to flutter or fibrillate. The end result is a lack of blood flow to all the organs (including the heart itself). If the person lives, it is often with a damaged heart.

Arrhythmias are mostly due to a decrease in oxygenation of the heart muscle and conduction system (decreased coronary perfusion).

Cardiomyopathy

As already mentioned, congestive heart failure is in itself not a diagnosis. Rather, it is the physiological result of damage to the heart caused by some antecedent disorder, for instance, cardiomyopathy.

Cardiomyopathy is a condition in which the muscle of the heart is damaged and no longer works properly. There are three kinds of myopathy. Dilated cardiomyopathy is often seen in people with alcohol use disorder or individuals with endocrine disorders. The heart muscle stretches and thins out and loses a lot of its reactivity.

In restrictive cardiomyopathy, the heart no longer moves properly; it is restricted. Restrictive cardiomyopathy is often the result of diabetes or prior heart surgery.

In contrast, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is seen coupled with high blood pressure and/or failure of the heart’s valves. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the cells of the heart enlarge and cause the walls of the ventricle (typically the left ventricle) to thicken.

Cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure go hand-in-hand, so much so that many textbooks and research papers clump them together in the same section (Sano et al. 2016).

Diabetes Mellitus

Congestive heart failure is traditionally thought of as a disorder experienced by older adults. When it is seen in the young, it is often coupled with type 2 diabetes.

Patients with diabetes are much more likely to develop CHF than patients without diabetes. Why? Many individuals with diabetes develop uncontrolled hyperglycaemia, hypertension and obesity. All of these factors lead to heart disease and, if not controlled, eventual failure.

Age-Related Deterioration

Even in the absence of disease, age-related changes in the heart and vascular system can lower the ‘threshold’ necessary for heart failure to occur.

As people age, the cardiac tissue stiffens and myocardial relaxation is prolonged, both of which lead to a decline in diastolic function, even in the healthy. Although diastolic function is the chief change seen with age, there is a modest disruption of systolic function as well.

These two factors combine to decrease peak exercise capacity every decade after age 30. This natural decline makes the body less able to buffet the storms brought about by hypertension, heart failure, renal insufficiency and all the other precursors just discussed.

Note that one of the main factors with age is hypertension. The artery walls become less elastic with age and can lead to CAD and ischaemic heart disease or plaque formation, resulting in cascade effects.

Common Precursors to Heart Failure in Summary

- Hypertension

- Renal insufficiency

- Damaged heart tissue (myocardial infarction)

- Coronary artery disease/ischaemia

- Abnormal heart valves

- Pulmonary embolus (PE) and hypertension

- Heart arrhythmias

- Cardiomyopathy

- Diabetes mellitus

- Age-related deterioration.

Note that this is not an exhaustive list. Other causes of congestive heart failure may include:

- Substance abuse

- Obstructive sleep apnoea

- Infections (myocarditis, endocarditis).

Topics

References

- Cahill, TJ & Kharbanda, RK 2017, ‘Heart Failure After Myocardial Infarction in the Era of Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Mechanisms, Incidence and Identification of Patients at Risk’, World Journal of Cardiology, vol. 9, no. 5, viewed 9 October 2023, https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v9/i5/407.htm

- Damman, K et al. 2017, ‘Progression of Renal Impairment and Chronic Kidney Disease in Chronic Heart Failure: An Analysis From GISSI-HF’, Journal of Cardiac Failure, vol. 23, no. 1, viewed 9 October 2023, https://onlinejcf.com/article/S1071-9164(16)31140-X/fulltext

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2022a, What Are Heart Valve Diseases?, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 9 October 2023, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/heart-valve-diseases

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2023, What Is Pulmonary Hypertension?, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 9 October 2023, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/pulmonary-hypertension

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2022b, What Is Venous Thromboembolism?, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 9 October 2023, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/venous-thromboembolism

- Pfeffer, MA 2017, ‘Heart Failure and Hypertension: Importance of Prevention’, Medical Clinics of North America, vol. 101, no. 1, viewed 9 October 2023, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S002571251637331X?via%3Dihub

- Sano, M, Homma, T, Ishige, T, Sawada, N, Ihara, S, Kinoshita, K, Masuda, S & Hao, 2016, ‘An Autopsy Case of Hyperthyroid Cardiomyopathy Manifesting Lethal Congestive Heart Failure’, Pathology International, vol. 67, no. 2, viewed 9 October 2023, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pin.12491/full

- Sudharshan, S, Novak, E, Hock, K, Scott, MG & Geltman, EM 2017, ‘Use of Biomarkers to Predict Readmission for Congestive Heart Failure’, The American Journal of Cardiology, vol. 119, no. 3, viewed 9 October 2023, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pin.12491/full

- Vyas, V & Goyal, A 2022, ‘Acute Pulmonary Embolism’, StatPearls, viewed 9 October 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560551/