Drinking alcohol prior to conception and during pregnancy can have significant adverse outcomes for the fetus, including miscarriage, premature birth or stillbirth (ADF 2022).

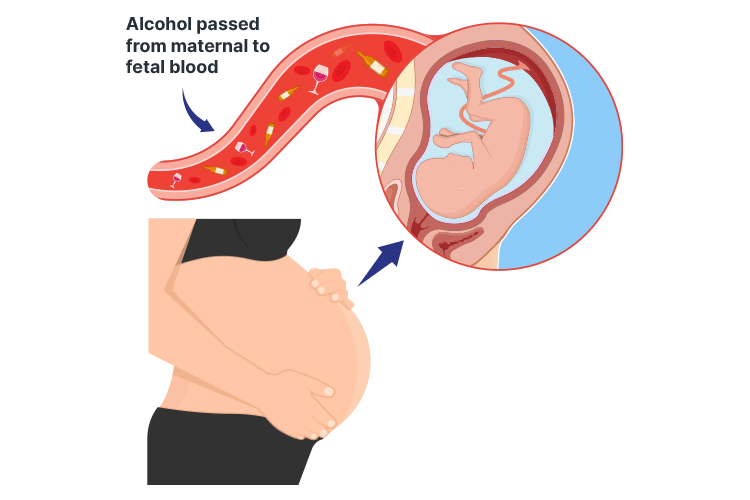

When alcohol is consumed during pregnancy, it enters the fetus’s bloodstream via the placenta and may impact the development of the fetus’s brain or other organs (Mayo Clinic 2024).

There is no known safe level of alcohol use during pregnancy, and it’s not possible to predict the extent to which a fetus will be affected by alcohol. For this reason, the safest option is to completely avoid alcohol prior to conception and during pregnancy (Every Moment Matters 2022).

Fetal alcohol syndrome disorder (FASD) is known to be associated with persistent physical and neurodevelopmental abnormalities (Vaux 2023). FASD crosses all socioeconomic groups and affects all races and ethnicities (Synapse 2024).

It’s a condition that is both disabling and entirely preventable.

What is Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder?

The term fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) describes a range of adverse effects that may occur following alcohol exposure during the prenatal period. These effects include physical, mental, behavioural and learning disabilities, and may have lifelong implications (Better Health Channel 2022).

While the prevalence of FASD in Australia is difficult to determine, it is estimated that up to 2% of babies may be born with a type of FASD (DoH 2023).

Diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

In order to be diagnosed with FASD in Australia, there must be evidence of prenatal alcohol exposure, and the individual must also display severe impairment in at least three of the following neurodevelopmental domains:

- Brain structure or neurology

- Motor skills

- Cognition

- Language

- Academic achievement

- Memory

- Attention

- Executive function (including impulse control and hyperactivity)

- Affect regulation

- Adaptive behaviour, social skills or social communication

(Bower & Elliott et al. 2020)

From here, there are two subcategories of an FASD diagnosis:

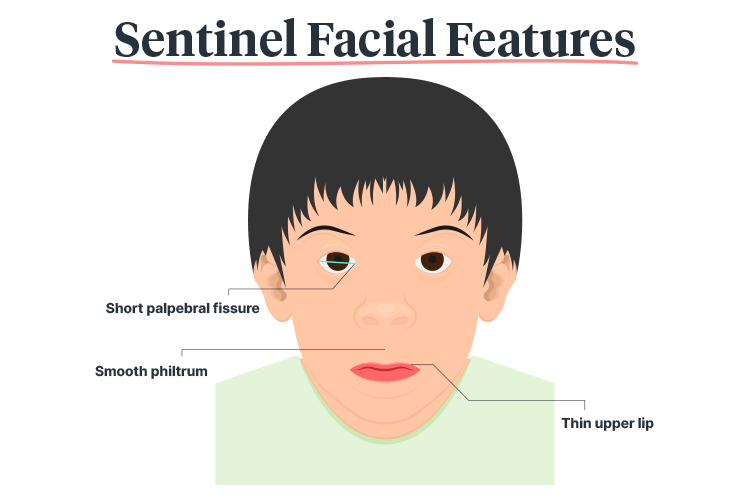

- FASD with three sentinel facial features (replacing the previous diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome)

- FASD with less than three sentinel facial features (replacing the previous diagnoses of partial fetal alcohol syndrome and neurodevelopmental disorder-alcohol exposed)

(Bower & Elliott et al. 2020)

These sentinel facial features include:

- Short palpebral fissure (i.e. reduced space between the open eyelids)

- Smooth philtrum

- Thin upper lip

(Bower & Elliott et al. 2020)

Nurses and Midwives Have an Important Role to Play

As Mitchell et al. (2018) suggest, nurses and midwives are in an ideal position to talk to people of reproductive age about the dangers of alcohol use during pregnancy.

In some cases, the prevention of alcohol-exposed pregnancies requires skilful conversations and appropriate follow-up to be clinically effective.

The fact remains that the all-important first step in reducing the incidence of FASD begins by asking about alcohol consumption and advising patients about its effects during pregnancy.

Just as with other forms of lifestyle advice, however, talking alone is often not enough to bring about a behavioural change. Wherever possible, people planning a pregnancy should also be assisted to stop their alcohol consumption and be offered further support, referral, follow-up and treatment where needed.

Make sure that the following guidance is provided:

- No amount of alcohol intake is considered safe during pregnancy

- There is no safe trimester for drinking alcohol

- All forms of alcohol pose similar risks

- Binge drinking poses a dose-related risk to the developing fetus

- FASD impairs executive functioning

- Alcohol damages critical brain functioning in the fetus

- FASD is irreversible

- There are resources and referrals available

(Williams & Smith 2015; Heath 2023)

Remember that there is no wrong time to screen or educate patients who may be at risk of drinking during pregnancy (Heath 2023).

Implications for Practice

As Eguiagaray et al. (2016) suggest, there is currently a pressing need for greater openness with patients to challenge the stigma of drinking alcohol during pregnancy.

Drinking in pregnancy is clearly a highly emotive issue that requires sensitive and careful management. On the one hand, delivering alcohol brief interventions (screening the patient for alcohol and drug use) (Rodgers 2018) at the first antenatal appointment is more likely to produce results, but it can also threaten to damage the relationship between midwife and patient.

Recognising this, Doi et al. (2015) suggest that when training midwives to screen and deliver alcohol brief interventions, special attention is needed to improve person-centred communication skills in order to overcome any barriers associated with discussing alcohol use.

Eguiagaray et al. (2016) go further by suggesting that guidelines for media reporting should also be revised to discourage stigmatising patients and that media articles should also consider the role that government, non-government organisations and the alcohol industry itself could play in improving FASD shame.

Alongside these suggestions are calls for more education and counselling to raise awareness of FASD. Larcher and Brierley (2014) recommend that this could also helpfully be part of a wider public health and social policy initiative on reducing alcohol consumption.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

What are the three sentinel facial features found in FASD?

Topics

References

- Alcohol and Drug Foundation 2022, ‘Alcohol and Pregnancy’, Insights, 13 September, viewed 18 July 2024, https://adf.org.au/insights/alcohol-and-pregnancy/

- Better Health Channel 2022, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), Victoria State Government, viewed 18 July 2024, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/ConditionsAndTreatments/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder-fasd

- Bower C, Elliott EJ 2020, On behalf of the Steering Group, Australian Guide to the Diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), Australian Government Department of Health, viewed 18 July 2024, https://www.fasdhub.org.au/fasd-information/assessment-and-diagnosis/guide-to-diagnosis/

- Department of Health 2023, National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Strategic Action Plan 2018-2028, Australian Government, viewed 18 July 2024, https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder-fasd-strategic-action-plan-2018-2028?language=en

- Doi, L, Jepson, R & Cheyne, H 2015, ‘A Realist Evaluation of an Antenatal Programme to Change Drinking Behaviour of Pregnant Women’, Midwifery, vol. 31, no. 10, pp. 965-72, viewed 18 July 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4596150/

- Eguiagaray, I, Scholz, B & Giorgi, C 2016, ‘Sympathy, Shame, and Few Solutions: News Media Portrayals of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders’, Midwifery, vol. 40, pp. 49-54, viewed 18 July 2024, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0266613816300894?via%3Dihub

- Every Moment Matters 2022, Alcohol and Pregnancy: An Evidence Summary, Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education, viewed 18 July 2024, https://everymomentmatters.org.au/wp-content/uploads/EMM_Fact_Sheet_Prenatal_alcohol_exposure_An_evidence_summary.pdf

- Heath, A 2023, ‘Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder’, Ausmed, 19 October, viewed 18 July 2024, https://www.ausmed.com.au/cpd/courses/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder

- Larcher, V & Brierley, J 2014, ‘Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)—Diagnosis and Moral Policing; An Ethical Dilemma for Paediatricians’, BMJ, vol. 99, no. 11, viewed 18 July 2024, http://adc.bmj.com/content/99/11/969

- Mayo Clinic 2024, Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, Mayo Clinic, viewed 18 July 2024, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/fetal-alcohol-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20352901

- Mitchell, A et al. 2018, ‘An Environmental Scan of the Role of Nurses in Preventing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders’, Issues in Mental Health Nursing, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 151-8, viewed 18 July 2024, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01612840.2017.1384873

- Rodgers, C 2018, ‘Brief Interventions for Alcohol and Other Drug Use’, Australian Prescriber, vol. 41, no. 4, viewed 18 July 2024, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6091783/

- Synapse 2024, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), Synapse, viewed 18 July 2024, https://synapse.org.au/creating-real-change/why-our-work-matters/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder-fasd/

- Vaux, KK 2023, Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, Medscape, viewed 18 July 2024, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/974016-overview

- Williams, J, Smith, V & The Committee on Substance Abuse 2015, ‘Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders’, Pediatrics, vol. 106, no. 2, p. 358, viewed 18 July 2024, https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/136/5/e20153113/33770/Fetal-Alcohol-Spectrum-Disorders