Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second-most common type of skin cancer after basal cell carcinoma (BCC), accounting for about 33% of skin cancers (Cancer Council Victoria 2022).

While cSCC is a less serious form of skin cancer than melanoma, it can grow quickly and spread, causing potentially serious complications if untreated (Cancer Council Victoria 2022; Mayo Clinic 2021).

However, If addressed early, cSCCs can be easily resolved in most cases (Hale & Hank 2023).

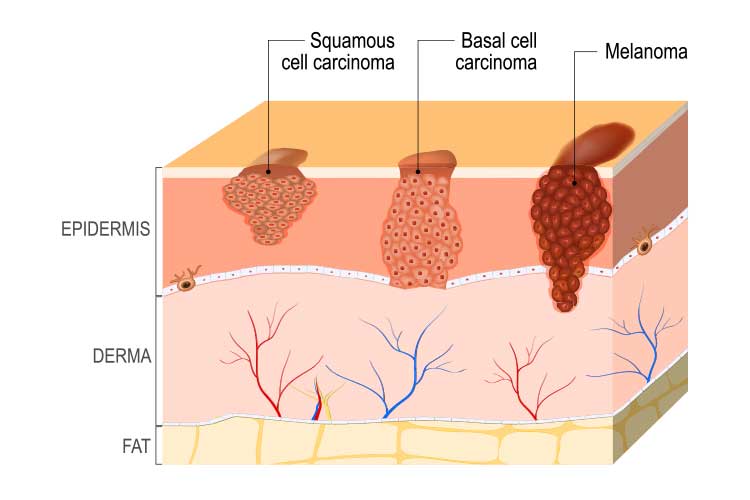

cSCC has several features distinguishing it from BCC and melanoma. Awareness of these differences can assist with timely referral and treatment, thereby reducing morbidity associated with aggressive tumours and enhancing overall patient outcomes. All healthcare professionals should be able to identify lesions and refer appropriately.

What is Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma?

cSCC is triggered by DNA mutation (caused by UV radiation or other factors) to the flat cells located in the upper layer of the epidermis, known as squamous cells. This mutation causes the squamous cells to grow and divide abnormally. cSCCs grow quickly over weeks or months (Cancer Council Victoria 2022; Hale & Hank 2023; Healthdirect 2023).

Squamous cells can be found in many parts of the body, all of which are susceptible to developing cSCC. However, in most cases, cSCCs appear on areas of skin that are most frequently exposed to UV radiation (Healthdirect 2023). These include:

- Face

- Lips

- Hands

- Ears

- Forearms

- Lower legs.

(Oakley 2015)

Bowen’s disease is a pre-cancerous form of cSCC that generally presents as a red, scaly patch. If unaddressed, it may develop into cSCC (Healthdirect 2023).

Note: While ‘cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma’ specifically refers to cancer of the skin, squamous cell cancers can also develop internally (e.g. in the mouth, throat or lungs). These are known as squamous cell carcinoma (SCCs) (Hale & Hank 2023).

Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma v Basal Cell Carcinoma v Melanoma

| Location of origin | Common physical characteristics | Growth and spread rate | Image | |

| cSCC | Squamous cells (upper layer of the epidermis) |

|

Grow and spreads quickly; generally not serious but can cause complications if untreated. |  |

| BCC | Basal cells (bottom layer of the epidermis) |

|

Grows slowly and is unlikely to spread; least serious type of skin cancer. |  |

| Melanoma | Melanocytes (pigment-making cells in the epidermis) |

|

Grows and spreads quickly; most serious type of skin cancer. |  |

(Cancer Council Victoria 2022; ACS 2019; SunSmart 2014)

Prevalence of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

There are over one million treatments performed anually for non-melanoma skin cancers in Australia. SCCs most commonly affect people over the age of 50 (Cancer Council Victoria 2022).

cSCC and BCC combined cause about 560 deaths annually (CCA 2019).

Risk Factors for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- Being male

- Being over the age of 50

- Fair complexion (particularly if the individual has freckles, blonde or red hair or blue or green eyes)

- History of skin cancer (cSCC or another type)

- Precancerous growths (e.g. actinic keratosis, actinic cheilitis, leukoplakia, Bowen’s disease)

- Direct ultraviolet (UV) exposure (either from the sun or artificial sources)

- History of sunburns

- Reduced immune function due to illness or immunosuppressive medications

- Exposure to ionising radiation or chemical carcinogens

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection

- Individual response to chronic inflammation (such as a burn site)

- Certain genetic disorders such as xeroderma pigmentosum.

(Hale & Hank 2023; Mayo Clinic 2021)

About 90% of cSCC cases can be attributed to UV exposure (Hale & Hank 2023).

Warning Signs of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

There are a number of signs to look for when identifying potential cSCCs, as they can present in a variety of ways. Surface changes may include:

- Thick, red, scaly patches that may bleed or crust

- Raised growths or lumps, possibly with a depression in the middle

- Raised areas or new sores on existing scar or ulcer sites

- Open sores (possibly with oozing or crusting) that do not heal, or heal and then reappear

- Wart-like growths

- Flat sores with crusting

- Cutaneous horn

- Keratoacanthoma

- Carcinoma cuniculatum.

(Hale & Hank 2023; Mayo Clinic 2021)

The lesion will generally range between a few millimetres to several centimetres in diameter and might be inflamed or tender (Oakley 2015).

Dysplasia

Dysplasia is the abnormal growth of a pre-existing lesion, from which cSCCs can develop. Initially, dysplastic keratinocytes above the epidermal basal layer behave abnormally, resulting in a focally thickened stratum corneum (SC); i.e. an actinic keratoses (AK) (Ratushny et al. 2012).

If the atypical keratinocytes demonstrate advancing dysplasia and dysfunction that fully infiltrates the epidermis, this becomes cSCC in situ, Bowen’s disease or intraepidermal carcinoma. A specific histological definition can highlight the lesion’s level of abnormality (Ratushny et al. 2012).

Well-differentiated cSCC’s most closely resemble normal tissue and are more predictable in behaviour than moderately well or poorly differentiated cSCCs, which are the most unpredictable tumours with poorer outcomes (Ratushny et al. 2012).

These less dysplastic, well-differentiated lesions retain some normal tissue function and can produce keratin, which may appear initially as a cutaneous horn (spiky, hard and often painful to the touch) (Ratushny et al. 2012).

Diagnosis and Treatment of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

A cSCC can be diagnosed through physical examination and biopsy if required (Mayo Clinic 2021).

The severity of the cSCC will dictate the appropriate treatment option. cSCCs and other cancers are often categorised using a staging system known as tumour-node-metastasis (TNM), which assesses three aspects of the cancer (EdCaN 2014):

- (T) Primary tumour

- Size of the tumour

- Whether any high-risk features are present (lesion is over a certain size, poor differentiation, growing around a nerve, on the lip or ear)

- Whether there is an invasion of facial or skeletal structures

- (N) Regional Lymph Nodes

- Whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes

- If so, the location, size and number of metastatic tumours

- (M) Metastasis

- Whether the cancer has spread to distant areas of the body.

(SkinCancer.net 2023)

A comprehensive explanation of the TNM staging system can be found on the Cancer Council Australia website.

Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Treatment

Treatment of cSCCs aims to completely remove the tumour in order to avoid recurrent disease or metastasis.

Depending on the patient’s characteristics, low-risk tumours (e.g. well defined, well-differentiated, small, thin and well-sited) can be treated with destructive modalities like curettage, cautery or topical creams.

High-risk tumours require complete excision. Challenging sites, e.g. thick, invasive lesions and lymph node involvement require a referral for comprehensive management (Hale & Hank 2023).

Conclusion

While cSCCs are not usually difficult to treat if addressed early, they have the potential to cause complications if left alone. Therefore, nurses working in all healthcare settings should have up-to-date knowledge of tumour types so that they can promptly identify cSCCs and determine the appropriate treatment for the patient.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

Which one of the following is NOT typically a physical feature of cSCC?

Topics

References

- American Cancer Society 2019, What Are Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers?, ACS, viewed 3 August 2023, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/basal-and-squamous-cell-skin-cancer/about/what-is-basal-and-squamous-cell.html

- Cancer Council Australia 2019, Keratinocyte Cancer: Prognosis, Cancer Council Australia, viewed 3 August 2023, https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:Keratinocyte_carcinoma/Prognosis

- Cancer Council Victoria 2022, Skin Cancer, Cancer Council Victoria, viewed 3 August 2023, https://www.cancervic.org.au/cancer-information/types-of-cancer/skin_cancers_non_melanoma/skin-cancer-overview.html

- EdCaN 2014, Cancer Grading and Staging, Australian Government, viewed 3 August 2023, http://edcan.org.au/edcan-learning-resources/supporting-resources/biology-of-cancer/cancer-signs-and-symptoms/grading-and-staging

- Healthdirect 2023, Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC), Australian Government, viewed 3 August 2023, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/squamous-cell-carcinoma

- Mayo Clinic 2021, Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin, Mayo Clinic, viewed 3 August 2023, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/squamous-cell-carcinoma/symptoms-causes/syc-20352480

- Hale, EK & Hank, CW 2023, Squamous Cell Carcinoma Overview, Skin Cancer Foundation, viewed 3 August 2023, https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/squamous-cell-carcinoma/

- Oakley, A 2015, Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma, DermNet NZ, viewed 3 August 2023, https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-squamous-cell-carcinoma

- Ratushny, V, Gober, MD, Hick, R, Ridky, TW & Seykora, JT 2012, ‘Keratinocyte to Cancer: The Pathogenesis and Modelling of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma’, The Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 122, no. 2, viewed 3 August 2023, http://doi.org/10.1172/JCI57415

- SkinCancer.net 2023, Stages of Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Health Union, viewed 3 August 2023, https://skincancer.net/types-signs/squamous-cell-carcinoma-stages

- SunSmart 2014, About Skin Cancer, SunSmart, viewed 3 August 2023, https://www.sunsmart.com.au/skin-cancer/about-skin-cancer