Why Reflection Matters

Healthcare workers all experience clinical practice moments where things haven’t gone as well as they feel they should have. Events where someone died, had an adverse outcome, mistakes were made, or where a situation dramatically escalated. As clinicians, we tend to dwell on these moments. This article explores how we can use reflective practice to learn from and move on from intense events, and how to learn from small positive moments that we might otherwise miss.

Reflecting on the Big Moments

Though reflective practice can take many forms, in clinical practice, reflection often takes the form of a conversation, like a clinical debrief. Hot and cold debriefs are common in teams after major events. A hot debrief happens immediately after, while a cold debrief occurs later. These sessions explore what went well, what could have been better, and how to improve. This aligns with reflective theories by Schön (1983) and Dewey (1933), which focus on reconstructing events to create future change.

Debriefs support clinical learning and can protect clinicians' mental health by providing a safe space to talk. However, they aren't always perfect. Hot debriefs can get quite heated and may not always feel therapeutic. How we reflect on an incident affects our ability to grow from it. No one wants to be kept up at night by past events, especially those working shifts with already compromised sleep.

Reflect on The Little Things

You can apply the hot/cold debrief concept to your personal reflections. Choose a moment from your day — an interaction with a patient or colleague, a shift, or anything in between. It doesn’t need to be dramatic to be worth reflecting on. Ask yourself:

- What went well?

- What could have gone better?

- What did I learn?

- What do I need to learn, improve, or change for next time?

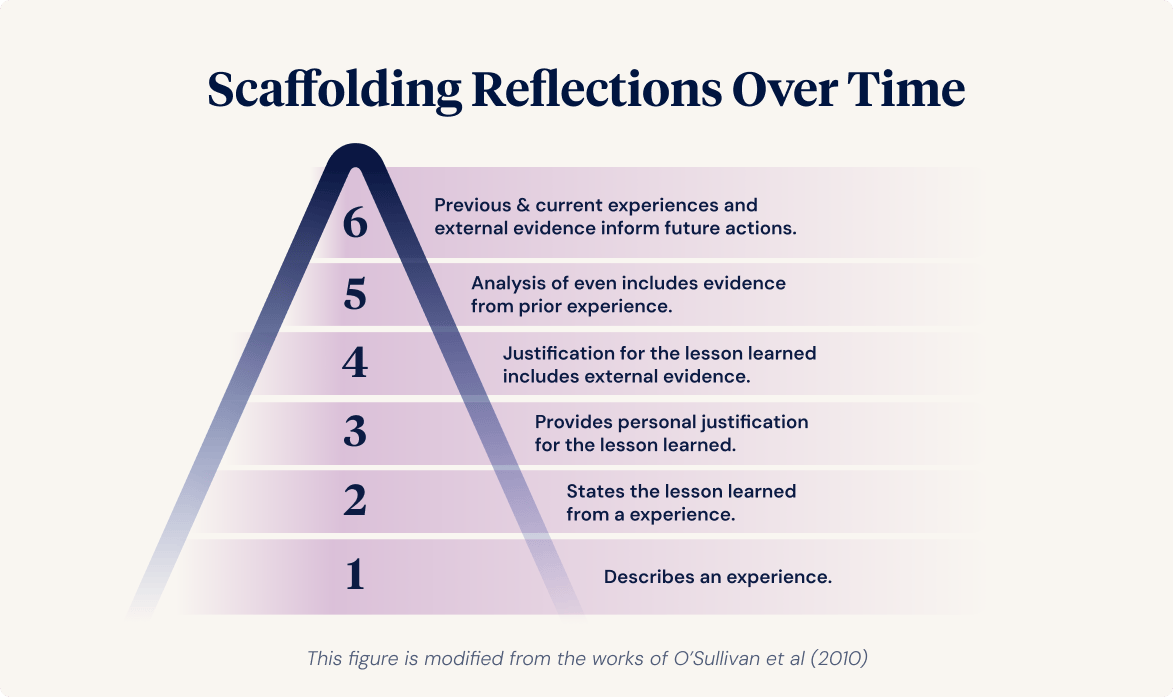

Over time, try to add depth and complexity to your reflections. To do this, it may be useful to use a simple scaffold (refer to image below). In the beginning, your reflections may be typically limited to levels 1-3, which revolve around describing and learning simple lessons from your experiences. Those new to reflection typically learn lessons based on their personal perspectives only. Over time, try to extend yourself to include more in your reflective process.

The ultimate goal of reflection is positive future change, which is based upon the event you’re focusing on, your other past events, and external evidence (e.g., views of colleagues, feedback from patients, professional reading, study). Ultimately, you’re aiming to “bridge the gap between the experience of an event and making sense of it” to influence your future practice.

Let time pass. Return to your reflections after a few days and reconsider them with fresh eyes. Have your thoughts changed? Use these follow-ups to focus on growth. "Next time, I will..." is more constructive than "I did this wrong." Reflection is about learning, not blame. Blame fosters self-doubt. Accountability matters, but so does recognising that mistakes and gaps are part of being human.

Reflection helps uncover what we don’t know and reinforces what we do well. It supports learning, highlights strengths, and promotes wellbeing by stopping unhelpful cycles of self-criticism. That’s what makes reflective practitioners safer and stronger.

Creating Reflection Opportunities

Reflection can happen anytime, on any experience. Sometimes after major events, sometimes on the little things. Both are vital to personal and professional development and to avoiding burnout.

Example Reflection

Here’s one from a shift in a rural emergency department:

It was a typical busy day in the emergency department. Constant patient turnover, struggling to keep up with tasks, and long wait times for test results. Patients often become heightened, inpatient, frustrated and sometimes aggressive and angry. We in ED know that these people are vulnerable, often scared or worried. It is therefore important that we ensure their basic needs are met, that they feel respected, heard, feel informed, are comfortable (have their pain under control, etc), and have food and fluids if their clinical condition allows. This isn’t always possible due to high workload, but nonetheless, we try to meet their needs. Recently, a colleague came to me and told me that a patient had asked her to pass on her gratitude for my help that day.

I reflected on the care I had provided for that patient on my drive home. I addressed her pain in a timely fashion and monitored it every time I did her vital signs. I updated her the best I could on where we were at and what was happening next, offered her food, fluids, blankets, and checked if she had any other needs, questions or concerns. Essentially, I did my job right. Reflecting on this event helped me understand what my patients really appreciated about the care I provide.

Some days it is easy to become task-oriented, but reflecting on that moment of gratitude and realising that I was appreciated that I was caring for the patient, their needs and not just performing clinical tasks, is a strong motivation and reminder that this is the right thing to do. This reflection may seem small but it was powerful for me to keep me patient-focused not task-focused, in the future because that’s what people appreciate and that's what makes a good clinician in healthcare.

Debriefing vs Individual Reflection

Reflection is often viewed as a private activity, but it can also be shared. Individual reflection might involve journaling, painting, mindfulness, or anything else that helps you process, identify strengths, and plan improvements. Team reflection, often through debriefing, happens after incidents to explore what happened and how to improve care.

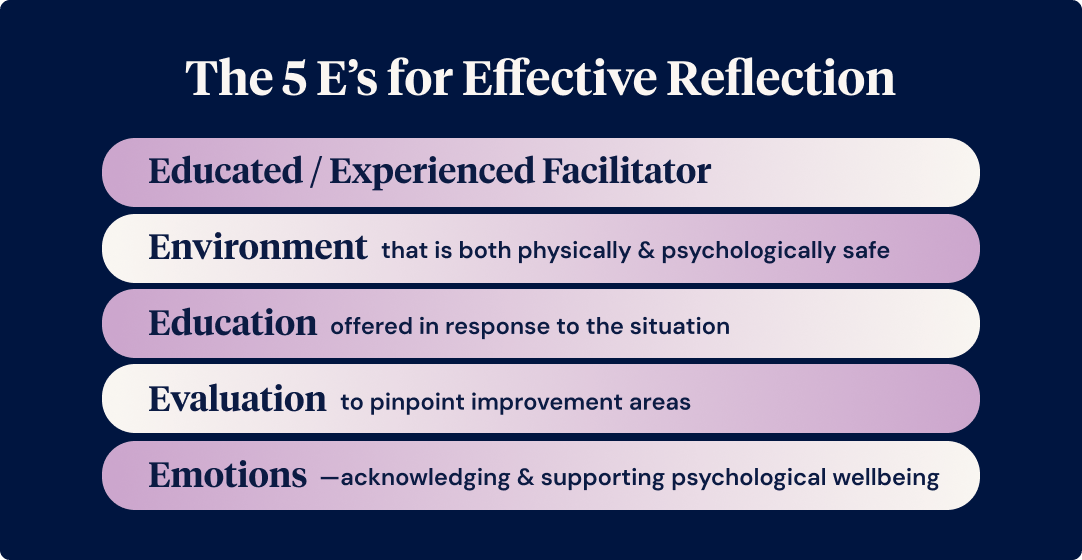

A facilitator usually guides the debriefing. The best debrief experiences follow the "5 E’s":

- Educated/Experienced facilitator

- Environment that is both physically and psychologically safe

- Education offered in response to the situation

- Evaluation to pinpoint improvement areas

- Emotions — acknowledging and supporting psychological wellbeing

If you’re new to reflection, try applying these principles independently. Be your facilitator. Choose a quiet, safe space. Think about what you learned, what you could improve, how you felt, and what you need going forward.

Your Daily Practice

It’s easy to focus on the undone tasks at the end of a shift. But reground yourself on what you did well. Healthcare is fast-paced, but reflection helps you stay connected to your purpose. Whether by debrief or solo practice, reflection should be daily. It highlights the good you bring, helps reframe the negatives, and can improve your wellbeing over time.

Want to learn more about reflection?

Listen to Episode 2 of Capability Corner! In this episode, we share a new Ausmed initiative around reflection.