Blood clots affect 30,000 Australians every year. They are potentially fatal if left untreated and account for about 10% of hospital deaths (Thrombosis Australia 2020).

As a healthcare professional, being able to recognise and manage blood clots is an essential skill that may save a patient’s life.

Note: While this article is a general overview of blood clots, it will focus on venous thromboembolism (VTE).

What is a Blood Clot?

A blood clot is a semisolid mass of blood components (platelets, proteins and cells) that clumps together in a process known as coagulation (i.e. the clotting mechanism) (Axtell 2022).

The blood components that form clots are referred to as ‘clotting factors’ (NHLBI 2022a).

Blood is essential for life as it delivers oxygen to the tissues and cells, and a significant loss of blood may be fatal. Coagulation, a component of haemostasis, is the body’s crucial mechanism to prevent significant blood loss when we are injured (Garmo et al. 2023; Streiff 2023).

Coagulation works by forming a clot to plug the blood vessel wall injury. Once the injured blood vessel has healed, the clot will generally dissolve on its own (Garmo et al. 2023; Streiff 2023).

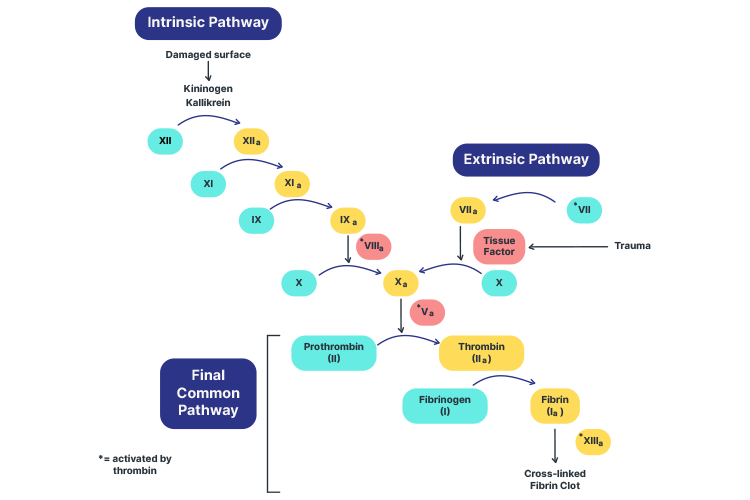

What is the Clotting Cascade?

The clotting cascade is a sequence of actions that occur upon the injury of a blood vessel in order to rapidly achieve haemostasis. It causes clotting factors to activate one after the other like a waterfall, resulting in the creation of a blood clot to plug the injury site until it has healed (Testing.com 2021; Chaudhry et al. 2023).

There are two stages of the clotting cascade:

- Primary haemostasis, where a weak platelet plug is formed in order to temporarily prevent haemorrhage until stability can be achieved through secondary haemostasis. It comprises four phases: vasoconstriction, platelet adhesion, platelet activation and platelet aggregation.

- Secondary haemostasis triggers the clotting cascade in order to stabilise the weak platelet plug that has been formed. There are two possible pathways for the cascade - intrinsic and extrinsic - both of which meet at the common pathway to finish the process.

(Garmo et al. 2023)

The intrinsic and extrinsic pathways have different triggers (Sreejith 2023).

The extrinsic pathway is the shorter of the two pathways (Chaudhry et al. 2023). It is activated in response to:

- Direct damage to the blood vessel

- Tissue damage outside of the blood vessel

- Hypoxia

- Sepsis

- Inflammation

- Malignancy.

(Reading 2023)

The intrinsic pathway is longer (Chaudhry et al. 2023). It is activated in response to:

- Direct damage to the blood vessel

- Collagen being exposed to platelets circulating in the blood.

(Reading 2023)

The extrinsic and intrinsic pathways then converge into the common pathway, stabilising the platelet plug (Chaudhry et al. 2023).

For more information, see Ausmed’s lecture on The Clotting Cascade..

Disruption to Haemostasis

While haemostasis is an essential physiological process, a delicate balance must be maintained between clotting factors that promote bleeding and those that promote coagulation (LaPelusa & Dave 2023).

If there is too much bleeding, the individual is at risk of losing excessive blood from a minor injury. On the other hand, if there is too much clotting, uninjured blood vessels can become plugged. Any abnormality in haemostasis may disrupt this balance, with potentially dangerous consequences (Streiff 2023).

Venous Thromboembolism

Note: A thrombus is a blood clot that forms in a vein or artery (Healthdirect 2023a).

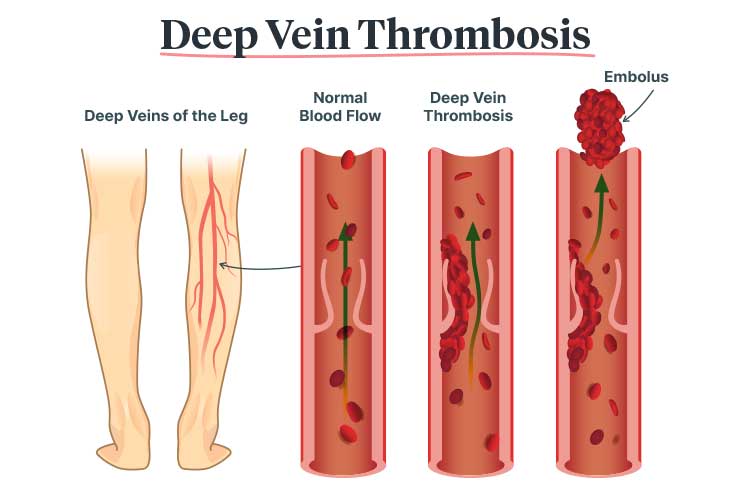

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurs when a thrombus forms inside healthy veins, obstructing normal blood flow (NHLBI 2022a).

The term VTE is used to describe two conditions:

(CDC 2025a)

DVT occurs when a thrombus forms in a deep vein. This can occur anywhere in the body but is most common in the lower leg, thigh, pelvis or arm. The most common symptoms are pain, swelling, warmth and discolouration in the affected area (CDC 2025a).

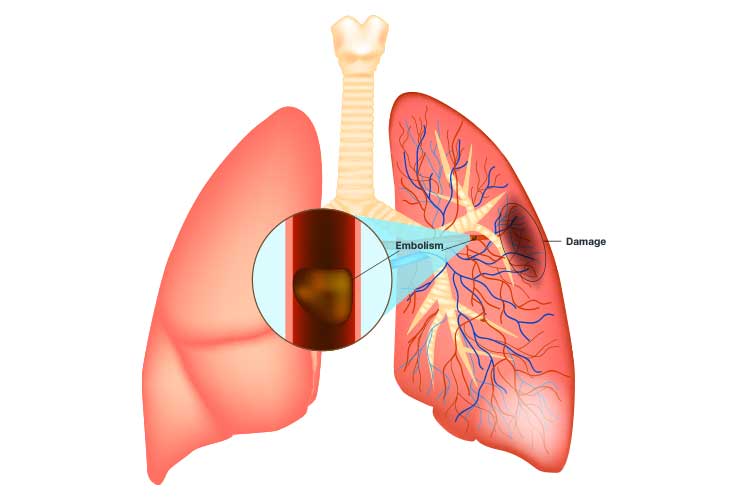

PE is a complication of DVT that occurs when the thrombus partially or completely dislodges and travels to the lungs. This is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication (CDC 2025a).

What is Virchow’s Triad?

Virchow’s triad describes the three primary risk factor categories for venous thromboembolism:

- Hypercoagulability (blood disorders that increase the risk of clotting), for example, an inherited Factor V Leiden mutation

- Abnormal blood flow, for example, stasis due to obesity or immobility

- Vessel wall injury (aka endothelial Injury), for example, damage from smoking or sepsis.

(Garmo et al. 2023; Kushner et al. 2024)

Risk Factors for Blood Clots

Specific risk factors include:

- Older age, partially due to increased risk of comorbidity

- Immobility due to prolonged travel (e.g. long-haul flights), prolonged surgery, post-surgical immobilisation or trauma

- Surgery, particularly major orthopaedic and neurovascular surgeries

- Previous blood clot

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Pregnancy (particularly during the postpartum period), which causes a hypercoagulable state (increased risk for those with a multiple pregnancy and people of a late maternal age)

- Cancer, which is associated with hypercoagulability

- Chronic conditions including atherosclerosis, heart failure, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, sepsis, COVID-19, tuberculosis, asthma, obstructive sleep apnoea, diabetes mellitus and others

- Chemotherapy

- Hormone therapy (including oral contraceptives)

- Having a central venous catheter in situ

- Inherited thrombophilias, such as Factor V Leiden mutation

- Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

(Healthdirect 2023b; McLendon et al. 2023)

Between 50 and 75% of hospitalised patients have at least one risk factor for VTE, and 40% have three or more (ACSQHC 2020).

Recognising a Blood Clot

See Ausmed’s Article on Pulmonary Embolism - DVT to PE for a more comprehensive explanation of how to recognise a clot.

Deep Vein Thrombosis

DVT symptoms may include:

- Pain and tenderness

- Pain when extending the affected area

- Swelling

- Warm skin

- Changes in skin colour in the affected area (e.g. red, pale or bluish skin).

(Better Health Channel 2023)

If the DVT occurs in a leg vein, these symptoms generally only affect one leg (NHS 2023).

Note that some people may not experience any symptoms (Healthdirect 2023b).

Pulmonary Embolism

The symptoms of PE can range from absent or mild to extremely severe, with the possibility of shock or sudden death (Vyas et al. 2024).

In fact, sudden death is the first clinical sign in one-quarter of patients (ACSQHC 2020).

This condition, therefore, requires urgent treatment.

Possible symptoms include:

- Shortness of breath, especially if it is new or sudden

- Increased respiratory rate and decreased oxygen saturation

- Pleuritic chest pain

- Cough or coughing up blood

- Loss of consciousness

- Hypotension

- Increased or irregular heart rate

- Sweating

- Fever

- Dizziness

- Clamminess.

(Healthdirect 2023c; Vyas et al. 2024)

Note that a PE can occur even without the presentation of DVT symptoms (CDC 2024).

About one-third of people who have had a VTE will experience another within the next 10 years (CDC 2025b).

Treating a Blood Clot

See Ausmed’s Article on Pulmonary Embolism - DVT to PE for information on how to treat a VTE.

Preventing a Blood Clot

Blood clots are a leading cause of preventable death in Australia (ACSQHC 2020).

Depending on the individual, prevention strategies may include:

- Smoking cessation

- Reducing alcohol consumption

- Losing weight

- Regular exercise

- Dietary changes

- Wearing compression stockings (must be properly fitted if worn and directed by your healthcare professional)

- Medicines such as anticoagulants

- Mobilisation after prolonged immobility (e.g. surgery, injury or travelling)

- Wearing loose-fitting clothes.

(Healthdirect 2023a; CDC 2025a)

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

Which one of the following conditions is included under the term venous thromboembolism (VTE)?

Topics

Further your knowledge

Free

Free

Free

FreeReferences

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2020, Venous Thromboembolism Prevention Clinical Care Standard, Australian Government, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/venous-thromboembolism-prevention-clinical-care-standard-2020

- Axtell, B 2022, ‘Blood Clot in Arm: Identification, Treatment, and More’, Healthline, 13 September, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.healthline.com/health/blood-clot-in-arm

- Better Health Channel 2023, Deep Vein Thrombosis, Victoria State Government, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/deep-vein-thrombosis

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2024, Understanding Your Risk for Blood Clots with Travel, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/blood-clots/risk-factors/travel.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2025a, About Venous Thromboembolism (Blood Clots), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/blood-clots/about/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2025b, Data and Statistics on Venous Thromboembolism, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/blood-clots/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

- Chaudhry, R, Usama, SM & Babiker, HM 2023, ‘Physiology, Coagulation Pathways’, StatPearls, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482253/

- Garmo, C, Bajwa, T & Burns, B 2023, ‘Physiology, Clotting Mechanism’, StatPearls, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507795/

- Healthdirect 2023a, Thrombosis, Australian Government, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/thrombosis

- Healthdirect 2023b, Blood Clots, Australian Government, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/blood-clots

- Healthdirect 2023c, Pulmonary Embolism, Australian Government, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/pulmonary-embolism

- Kushner, A, West, WP, Khan Suheb, MZ & Pillarisetty, LS 2024, ‘Virchow Triad’, StatPearls, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539697/

- LaPelusa, A & Dave, HD 2023, ‘Physiology, Hemostasis’, StatPearls, viewed 12 May 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545263/

- Testing.com 2021, Coagulation Cascade, OneCare Media, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.testing.com/tests/coagulation-cascade/

- McLendon, K & Goyal, A 2023, ‘Deep Venous Thrombosis Risk Factors’ StatPearls, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.statpearls.com/ArticleLibrary/viewarticle/20300

- Sreejith, N 2023, Coagulation, TeachMe Physiology, viewed 22 May 2025, https://teachmephysiology.com/immune-system/haematology/coagulation/

- Streiff, MB 2023, How Blood Clots, MSD Manual, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-au/home/blood-disorders/blood-clotting-process/how-blood-clots

- National Health Service 2023, DVT (Deep Vein Thrombosis), NHS, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/deep-vein-thrombosis-dvt/

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2022a, How Does Blood Clot?, National Institutes of Health, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/clotting-disorders/how-blood-clots

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2022b, What Is Venous Thromboembolism?, National Institutes of Health, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/venous-thromboembolism

- Thrombosis Australia 2020, What is Thrombosis?, Perth Blood Institute, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.pbi.org.au/what-is-thrombosis

- Reading, J 2023, ‘The Clotting Cascade’, Ausmed, 28 February, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.ausmed.com.au/cpd/lecture/coagulation

- Vyas, V, Sankari, A & Goyal, A 2024, ‘Acute Pulmonary Embolism’, StatPearls, viewed 22 May 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560551/