What is Glomerulonephritis?

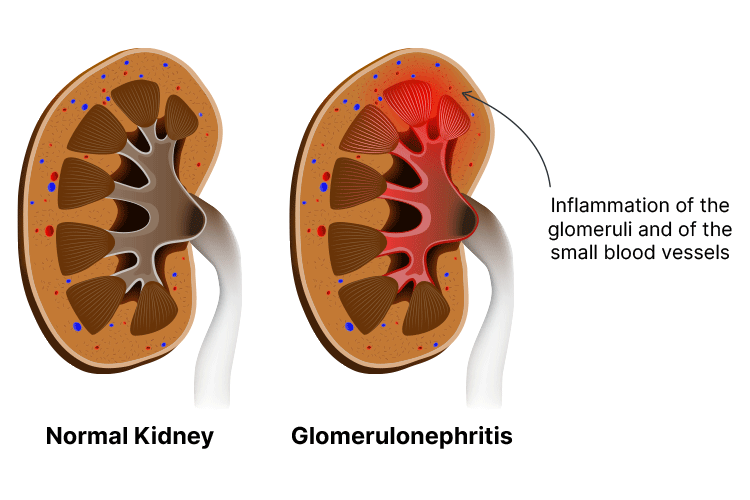

Glomerulonephritis is an umbrella term describing a variety of conditions that cause damage to and inflammation of the glomeruli - the filtering units in the kidneys (NKF 2025; Niaudet et al. 2023).

The glomeruli are clusters of microscopic blood vessels in the kidneys that filter blood through small pores to remove excess fluid and waste, which is later expelled as urine (O’Brien 2025a; Mayo Clinic 2024).

Glomerulonephritis prevents the glomeruli from properly filtering the blood, causing excess fluid and waste to accumulate in the body. This may eventually result in kidney failure (NKF 2025).

In most cases, glomerulonephritis occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the glomeruli. This can be triggered by a variety of potential underlying causes (Hazell 2023).

Glomerulonephritis can be acute or chronic, and may develop on its own or be secondary to a pre-existing condition (NKF 2025; Kazi & Hashmi 2023).

Causes of Glomerulonephritis

Acute Glomerulonephritis

Acute glomerulonephritis is often triggered by a previous infection, most commonly, a group A Streptococcus infection such as strep throat, scarlet fever or impetigo. This is known as post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (PSGN) and typically develops one to two weeks after recovering from the initial infection (Mayo Clinic 2024; CDC 2024).

PSGN is most common in children between the ages of 3 and 12 and older adults over 60 (Rawla et al. 2022). Children living in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are at increased risk of PSGN (myDr 2020).

Other infections that may trigger glomerulonephritis include:

- Endocarditis

- Hepatitis B

- Hepatitis C

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- Staphylococcus or pneumococcus infections

- Chickenpox

- Malaria.

(NHS 2023; O’Brien 2025a)

Glomerulonephritis triggered by an infection is believed to be the result of the immune system overreacting to the infection and is known as postinfectious glomerulonephritis (Case-Lo 2025; O’Brien 2025a).

Other potential triggers of acute glomerulonephritis include certain non-infectious illnesses such as lupus, Goodpasture syndrome and vasculitis, and in some cases, taking certain medicines, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Mayo Clinic 2024; Hazell 2023).

Chronic Glomerulonephritis

In many cases, the exact cause of chronic glomerulonephritis is unknown (O’Brien 2025a).

Some people who experience an acute episode of glomerulonephritis will go on to develop chronic illness in the future (NKF 2025).

Other potential triggers include:

- Hereditary nephritis (Alport syndrome) - a genetic condition that results in glomerulonephritis as well as other symptoms such as deafness and vision impairment

- Certain immune conditions that may also trigger acute glomerulonephritis

- Diabetes, which can cause diabetic nephropathy (scarring of the glomeruli)

- History of cancer

- Exposure to certain hydrocarbons, such as certain paints, paint removers and oils.

(Case-Lo 2025; O’Brien 2025a, b; Mayo Clinic 2024; Curtis et al. 2023)

Symptoms of Glomerulonephritis

Acute Glomerulonephritis

Acute glomerulonephritis typically has a sudden onset, with initial symptoms including:

- Facial puffiness (caused by oedema)

- Haematuria (blood in urine)

- Reduced urinary frequency

- Shortness of breath and coughing caused by pulmonary oedema

- Hypertension.

(NKF 2025; O’Brien 2025a; Case-Lo 2025)

However, about half the people with acute glomerulonephritis don’t experience any symptoms (O’Brien 2025a).

Chronic Glomerulonephritis

Chronic glomerulonephritis, on the other hand, may progress over a number of years without any obvious symptoms (NKF 2025).

Symptoms may include:

- Haematuria

- Proteinuria (protein in urine)

- Bubbly or foamy urine

- Hypertension

- Swelling in the face or ankles

- Frequent urination during the night

- Abdominal pain.

(Case-Lo 2025)

Kidney Failure

If glomerulonephritis progresses to kidney failure, the person will experience:

- Reduced appetite

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fatigue

- Sleeping issues

- Breathing difficulties

- Dry, itchy skin

- Muscle cramps at night.

(NKF 2025; O’Brien 2025a)

Complications of Glomerulonephritis

In addition to kidney failure, glomerulonephritis can potentially lead to:

- Chronic kidney disease

- Nephrotic syndrome - a condition where there is excessive protein in urine and inadequate protein in the bloodstream, causing high cholesterol, hypertension and swelling

- Electrolyte imbalances

- Chronic urinary tract infections

- Congestive heart failure (caused by retained fluid or fluid overload)

- Pulmonary oedema (caused by retained fluid or fluid overload)

- Hypertension

- Malignant hypertension

- Increased risk of infection

- Blood clot in a kidney blood vessel (caused by nephrotic syndrome).

(Mayo Clinic 2024; Case-Lo 2025)

Diagnosing Glomerulonephritis

Glomerulonephritis is typically diagnosed using:

- Urine tests to detect haematuria and proteinuria

- Blood tests to measure creatinine (a waste product filtered by the kidneys) levels in the blood

- Kidney biopsy to help determine the cause of the glomerulonephritis, assess the amount of scarring in the kidneys and determine whether the damage can be reversed

- Imaging (X-ray, ultrasound or CT scan).

(Cleveland Clinic 2023; O’Brien 2025a; Mayo Clinic 2024)

In cases of acute glomerulonephritis, additional tests might be performed in order to identify the specific cause. These might include:

- Throat culture to detect streptococcal infection

- Blood tests to detect raised levels of streptococci antibodies

- Cultures and blood tests to determine specific pathogens that have caused an initial infection

- Blood tests to detect autoantibodies (antibodies directed towards the body’s own tissue) and tests to assess the complement system (protein system involved in the immune system), if an autoimmune cause is suspected.

(O’Brien 2025a)

People with earlier stages of chronic glomerulonephritis may feel perfectly fine and experience no symptoms - the glomerulonephritis may only be discovered if a urine test reveals haematuria or proteinuria. For this reason, it’s often difficult to determine when exactly glomerulonephritis started (O’Brien 2025a).

Kidney biopsy is the most reliable way to confirm a glomerulonephritis diagnosis and exclude other kidney disorders, but it’s difficult to perform in later stages of the illness as the kidneys are too scarred and shrunken to reveal specific information (O’Brien 2025a).

Treating Glomerulonephritis

Specific treatment will depend on:

- Whether the glomerulonephritis is acute or chronic

- The underlying cause of the glomerulonephritis

- The type and severity of symptoms.

(Mayo Clinic 2024)

Acute Glomerulonephritis

Acute glomerulonephritis may resolve on its own without treatment (Mayo Clinic 2024). Cases triggered by a bacterial infection can’t typically be treated using antibiotics, because in most cases, the initial infection has already resolved by the time postinfectious glomerulonephritis occurs (O’Brien 2025a).

Cases triggered by other factors may be treated by addressing the underlying cause, for example, by administering corticosteroids if the glomerulonephritis is caused by an autoimmune disorder, or by treating hypertension if it is present (O’Brien 2025a).

Until kidney function is restored, people may also need to temporarily reduce their sodium and protein intake and take diuretics to help expel excess water and sodium (O’Brien 2025a).

Most children recover from acute glomerulonephritis within several weeks or months without further issues, however, adults might take longer to recover (myDr 2020).

Chronic Glomerulonephritis

Chronic glomerulonephritis may be managed by:

- Taking angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) to reduce blood pressure and proteinuria

- Reducing sodium and potassium intake

- Reducing protein intake to decrease the rate of kidney deterioration

- Reducing fluid intake and taking diuretics to help excess water and sodium be expelled

- Taking calcium supplements, as kidney disease disrupts the body’s bone and mineral metabolism

- Regularly exercising to help control hypertension.

(Case-Lo 2025; O’Brien 2025a; NKF 2025; myDr 2020; Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital 2017; Hill Gallant & Spiegel 2017)

In later stages of kidney failure, the person will require dialysis or a kidney transplant (O’Brien 2025a).

Preventing Glomerulonephritis

It’s not always possible to prevent glomerulonephritis, but it may be helpful to:

- Treat streptococcal infections promptly

- Reduce the risk of contracting infections that could trigger glomerulonephritis (e.g. HIV and hepatitis) by having safe sex and avoiding intravenous drug injection

- Controlling hypertension to reduce the risk of kidney damage

- Control blood sugar to help prevent diabetic nephropathy

- Maintain a healthy, low-salt diet

- Exercise regularly

- Undergo regular kidney screening, particularly if at increased risk of kidney disease (i.e. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and those who have hypertension, cardiovascular disease or diabetes).

(Mayo Clinic 2024; mrDr 2020)

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

True or false: Chronic glomerulonephritis is often asymptomatic in early stages.

Topics

References

- Case-Lo, C 2025, ‘Glomerulonephritis (Bright's Disease)’, Healthline, 29 April, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.healthline.com/health/glomerulonephritis

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2024, Post-Streptococcal Glomerulonephritis: All You Need to Know, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/group-a-strep/about/post-streptococcal-glomerulonephritis.html

- Cleveland Clinic 2023, Glomerulonephritis (GN), Cleveland Clinic, viewed 7 May 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16167-glomerulonephritis-gn

- Curtis, J, Metheny, E & Sergent, SR 2023, ‘Hydrocarbon Toxicity’, StatPearls, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499883/

- Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital 2017, Recovery & Support for Glomerulonephritis in Children, 2022 NYU Langone Health, viewed 7 May 2025, https://nyulangone.org/conditions/glomerulonephritis-in-children/support

- Hazell, T 2023, Glomerulonephritis, Patient, viewed 7 May 2025, https://patient.info/kidney-urinary-tract/glomerulonephritis-leaflet

- Hill Gallant, KM & Spiegel, DM 2017, ‘Calcium Balance in Chronic Kidney Disease’, Curr Osteoporos Rep., vol. 15, no. 3, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5442193/

- Kazi, AM & Hashmi, MF 2023, ‘Glomerulonephritis’, StatPearls, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560644/

- Mayo Clinic 2024, Glomerulonephritis, Mayo Clinic, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/glomerulonephritis/symptoms-causes/syc-20355705

- myDr 2020, Glomerulonephritis, myDr, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.mydr.com.au/glomerulonephritis/

- National Health Service 2023, Glomerulonephritis, NHS, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/glomerulonephritis/

- National Kidney Foundation 2025, Glomerulonephritis, NKF, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.kidney.org/atoz/content/glomerul

- Niaudet, P 2023, Overview of the Pathogenesis and Causes of Glomerulonephritis in Children, UpToDate, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-pathogenesis-and-causes-of-glomerulonephritis-in-children

- O’Brien, F 2025a, Glomerulonephritis, MSD Manual, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-au/home/kidney-and-urinary-tract-disorders/kidney-filtering-disorders/glomerulonephritis

- O’Brien, F 2025b, Alport Syndrome, MSD Manual, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.msdmanuals.com/en-au/home/kidney-and-urinary-tract-disorders/kidney-filtering-disorders/alport-syndrome

- Rawla, P, Padala, SA & Ludhwani, D 2022, ‘Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis’, StatPearls, viewed 7 May 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538255/