Somewhere in the world, a person dies every four minutes from postpartum haemorrhage (Smith 2022).

As well as being a terrifying experience for the birthing parent, postpartum haemorrhage can also be one of the most serious and alarming emergencies that a midwife has to manage.

So, can the risks of postpartum haemorrhage occurring be accurately assessed?

What is Postpartum Haemorrhage?

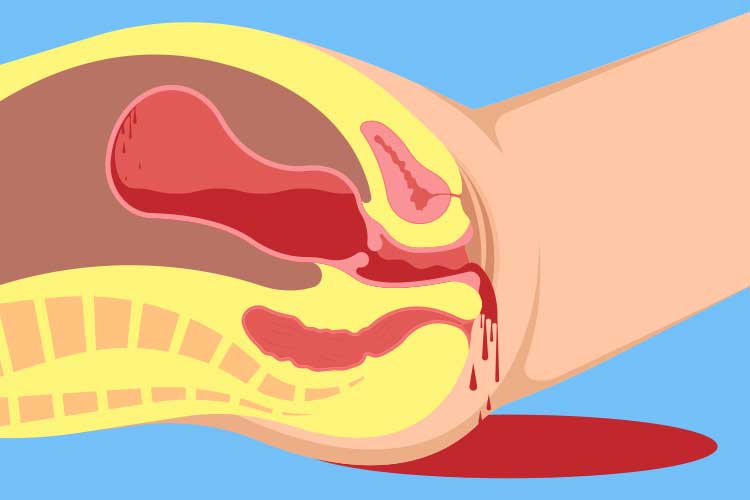

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is a potentially serious obstetric complication wherein a patient bleeds excessively after giving birth (RANZCOG 2021).

Some level of postpartum bleeding is normal. However, heavy bleeding is a potentially life-threatening event and requires immediate intervention (Pregnancy, Birth and Baby 2022).

About 5 to 15% of births in Australia and New Zealand result in PPH. While most of these cases are minor, PPH is associated with 70,000 deaths globally every year and is a leading cause of birth-related mortality in Australia and New Zealand (RANZCOG 2021; WHO 2022).

Primary PPH is defined as excessive bleeding within the first 24 hours of birth. This can be either:

- The loss of more than 500 mL of blood following vaginal birth

- Minor: 500 mL to 1 litre

- Major: More than 1 litre

- The loss of more than 1 litre of blood following a caesarean birth, or

- Enough blood loss to cause the birthing parent’s condition to deteriorate.

(QAS 2021; RANZCOG 2021)

Note: The definition of PPH may vary. Always refer to your organisation's policy.

Secondary PPH is defined as a loss of more than 500 mL of blood between 24 hours postpartum and 12 weeks postpartum (The Women’s 2020).

Risk Factors for Postpartum Haemorrhage

PPH is common and difficult to predict, so all people giving birth should be considered at risk of this complication (RANZCOG 2021). While most PPH incidents have no identifiable risk factors (RANZCOG 2021), the following factors may play a role in PPH:

- Multiparity

- Being over 35 years of age

- Having a very long or fast labour

- Induction of labour

- Having an operative delivery

- Having an episiotomy

- Giving birth to a large baby

- A stretched uterus (e.g. due to multiple pregnancy, macrosomia or excessive amniotic fluid)

- Having a bleeding disorder

- Previous history of PPH

- Having a caesarean birth

- Antepartum haemorrhage

- Placenta accreta

- Anaemia

- Pre-eclampsia

- Obesity

- Hypertension

- Diabetes

- Placental retention

- Infection

- Fibroids

(Pregnancy, Birth and Baby 2022; QAS 2021; SCV 2018)

Causes of Postpartum Haemorrhage

The most common cause of PPH is uterine atony (SCV 2018), wherein the uterine muscles do not contract properly post-birth. Usually, the uterus will contract to deliver the placenta and then compress the blood vessels that were attached to it. However, if these contractions are too weak, the blood vessels are able to bleed freely, potentially leading to haemorrhage (Cafasso & Galan 2016; Stanford Children’s Health 2014).

Uterine atony is associated with about 70% of PPH incidences. Referred to as ‘tone’, it comprises one of the ‘Four Ts’, which are the most common causes of PPH (Queensland Government 2023).

As well as ‘tone’, the Four Ts also include:

- Trauma (20% of PPH incidents), which includes:

- Lacerations of the cervix, vagina or perineum

- Extension lacerations during caesarean birth

- Uterine rupture or inversion

- Non-genital tract trauma

- Tissue (10% of PPH incidents), which includes:

- Retained products, placenta, membranes or clots

- An abnormal placenta

- Thrombin (less than 1% of PPH incidents), which is caused by issues with coagulation.

(QLD DoH 2023)

During an active PPH, the aim should be to manage the Four Ts. A fifth T, Theatre/Transport, represents the importance of getting the patient to a surgical facility for treatment (QAS 2021).

Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Postpartum Haemorrhage

It is important to note that a patient may not display symptoms of PPH until the blood loss has exceeded 1 litre, as the physiological changes of pregnancy may obscure the signs of haemodynamic instability (QAS 2021).

However, estimates of blood loss at delivery can be subjective and often inaccurate, with a tendency for healthcare staff to underestimate blood loss. Large volumes of blood can soak into bed linen and solidified clots may only represent about half of the actual blood that has been lost (Smith 2022).

Smith (2022) suggests that another consideration in assessing the risks of PPH is the differing capacities of individual patients to cope with blood loss. A healthy person has a 30 to 50% increase in blood volume in a normal singleton pregnancy and is much more tolerant of blood loss than a patient who has pre-existing anaemia, an underlying cardiac condition or a condition secondary to dehydration or pre-eclampsia.

Patients with a low body mass index also have a lower blood volume and tend to have fewer reserves to withstand significant blood loss and so, are likely to experience adverse physiological effects sooner. For these reasons, it’s suggested that PPH should be diagnosed when any amount of blood loss, however small, threatens the haemodynamic stability of the patient.

Symptoms to look out for include:

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Vaginal bleeding, possibly torrential and uncontrolled

- Signs of shock

- Restlessness

- Abnormally large and soft-feeling uterus.

(Queensland Government 2023; QAS 2021)

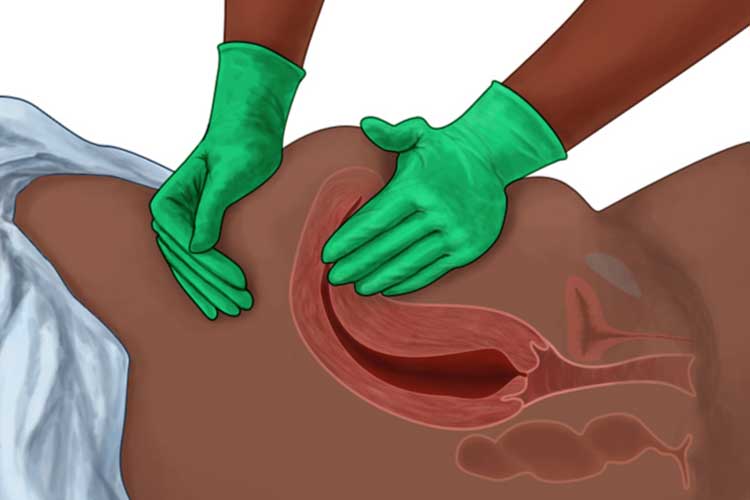

The Role of Fundal Massage

Fundal massage, also known as uterine massage, is a technique used to encourage the uterus to contract properly after delivery of the placenta. It involves applying repetitive massaging or squeezing motions to the woman’s abdomen in order to stimulate the uterus (Hofmeyr et al. 2013).

Australian clinical guidelines indicate the conditional use of fundal massage if the PPH is caused by uterine atony or a tissue problem (retained products or abnormal placenta) (QAS 2021; RANZCOG 2021; The Women’s 2020).

When treating a patient with PPH, a fundal massage should only be performed if the uterus is soft. A uterus that is firm, central and contracting properly does not require massaging; this may worsen bleeding or disrupt the normal placental separation post-birth (QAS 2021).

Can Anything be Done to Prevent Postpartum Haemorrhage?

Whilst identification of risk factors antenatally and intrapartum can be useful in the management of PPH, it is often unpredictable (Pregnancy, Birth and Baby 2022).

Those with identified risk factors may be administered medicine to help induce uterine contraction and delivery of the placenta (Pregnancy, Birth and Baby 2022).

Ultimately, it is only with anticipation, comprehensive policies on the management of obstetric emergencies, and prompt mobilisation of resources that lives can be saved.

Note: This article is intended as a refresher and should not replace best-practice care. Always refer to your organisation's policy on fundal massage and management of PPH.

Topics

References

- Cafasso, J & Galan, N 2016, ‘Atony of the Uterus’, Healthline, 9 February, viewed 20 November 2023, https://www.healthline.com/health/pregnancy/complications-delivery-uterine-atony

- Hofmeyr, G, Abdel-Aleem, H & Abdel-Aleem, M A 2013, ‘Uterine Massage for Preventing Postpartum Haemorrhage’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, no. 7, viewed 20 November 2023, https://www.cochrane.org/CD006431/PREG_uterine-massage-preventing-postpartum-haemorrhage

- Pregnancy, Birth and Baby 2022, Postpartum Haemorrhage, Healthdirect, viewed 20 November 2023, https://www.pregnancybirthbaby.org.au/postpartum-haemorrhage

- Queensland Ambulance Service 2021, Clinical Practice Guidelines: Obstetrics/Primary Post-partum Haemorrhage, Queensland Government, viewed 20 November 2023, https://www.ambulance.qld.gov.au/docs/clinical/cpg/CPG_Primary%20postpartum%20haemorrhage.pdf

- Queensland Health 2023, Primary Postpartum Haemorrhage, Queensland Government, viewed 20 November 2023, https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/140136/g-pph.pdf

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 2021, Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH), RANZCOG, viewed 20 November 2023, https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Management-of-Postpartum-Haemorrhage-PPH.pdf

- Safer Care Victoria 2018, Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH) – Prevention, Assessment and Management, Victoria State Government, viewed 20 November 2023, https://www.safercare.vic.gov.au/best-practice-improvement/clinical-guidance/maternity/postpartum-haemorrhage-pph-prevention-assessment-and-management

- Smith, JR 2022, Postpartum Hemorrhage, Medscape, viewed 20 November 2023, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/275038-overview

- Stanford Children’s Health 2014, Postpartum Hemorrhage, Stanford Children’s Health, viewed 20 November 2023, https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=postpartum-hemorrhage-90-P02486

- The Women’s 2020, Guideline Postpartum Haemorrhage, The Royal Women’s Hospital, viewed 20 November 2023, https://thewomens.r.worldssl.net/images/uploads/downloadable-records/clinical-guidelines/postpartum-haemorrhage_280720.pdf

- World Health Organisation 2022, WHO Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH) Summit, WHO, viewed 20 November 2023, https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-postpartum-haemorrhage-(pph)-summit